Jakarta: PonteSud – News Desk

This idea was born from the grand vision of Pierre de Coubertin, founder of the modern Olympic Games. He was inspired by the spirit of Ancient Greece, which celebrated both physical strength and artistic expression.

In Coubertin’s view, a true Olympian should not only be physically strong but also possess a deep artistic soul. That belief led to the ambition of merging sports and the arts into a single global platform: the Olympics.

Between 1912 and 1948, artists from around the world competed in five main categories: architecture, painting, sculpture, music, and literature. But there was a catch – every submitted work had to be directly related to the theme of sports or the Olympic spirit. For example, a musical piece evoking athletic competition, an epic poem celebrating victory, or a revolutionary stadium design.

Each category had its own set of specific rules. In literature, for instance, entries had a maximum word count of 20,000. Music submissions had to be no longer than one hour.

Despite sounding niche, the competition was taken very seriously. Gold, silver, and bronze medals were awarded – just like in the sporting events.

Imagine if the art competitions still existed today. Someone like LeRoy Neiman might be the “Michael Phelps” of painting. Or we could hear a gold-medal-winning song titled “The Ballad of Tonya and Nancy”, inspired by the infamous figure skating scandal.

The main issue was the professional vs. amateur debate. At the time, the Olympics only allowed amateur participants – in both sports and art. This posed a major problem, since most accomplished artists were already professionals and therefore disqualified.

As a result, few well-known artists ever competed. Many winners came from relatively unknown names, such as American architect Charles Downing Lay or lithographer Joseph Webster Golinkin, who also designed postage stamps.

Compounding the problem, poor documentation and lack of public interest led many of the winning artworks to be lost to history. Olympic historian Bernhard Kramer once noted that most of the art competition winners can no longer be traced. Titles like “Horseman” by Westermann are now little more than names in forgotten records.

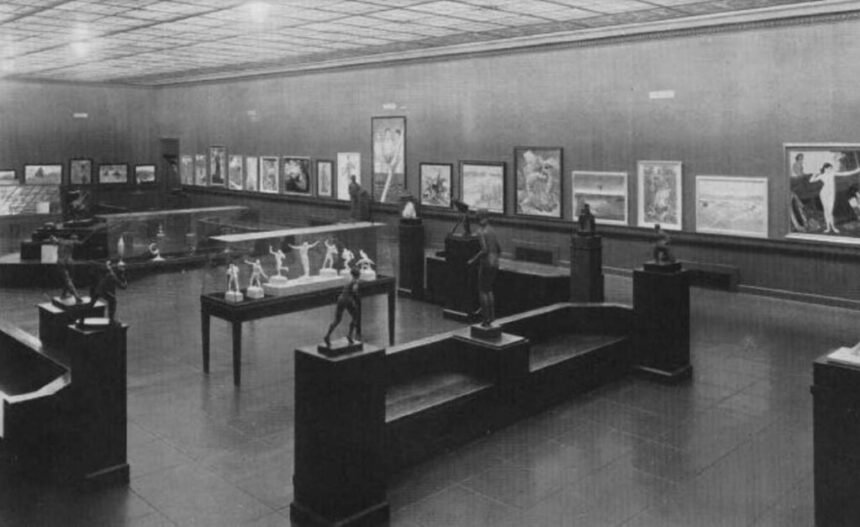

One of the most well-documented Olympic art competitions took place during the 1936 Berlin Olympics. At the opening ceremony, Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels emphasized that all submitted works must have been created within the past four years to reflect the current international climate.

With a judging panel dominated by 29 Germans out of 41 total members, it was no surprise that German artists swept the competition – winning five out of nine gold medals. Even the Olympic Stadium, designed by Werner March and his brother Walter, won gold in the architecture category.

Ironically, public enthusiasm in Germany for the art competition was low. Registration deadlines had to be extended, as many countries hesitated to participate due to global political tensions. Fortunately, this extension gave American artists based in Paris the opportunity to join.

Over a span of four weeks, more than 70,000 people visited the Olympic art exhibition in 1936. Notable figures such as Joseph Goebbels and Japanese diplomat Baron Morimoura even purchased artworks from the event.

After the 1948 Olympics in London, the art competitions were officially discontinued. The reason remained the same: it was too difficult to clearly separate amateur from professional artists. Unlike sports, the art world was far less accepting of restrictions on professional participation.

Though the competitions were scrapped, art continued to be part of the Olympic movement through the Cultural Olympiad – a program held every four years leading up to the Games. For example, the London 2012 Cultural Olympiad hosted more than 180,000 artistic events and drew 43 million participants.

Over four decades, more than 1,800 artists competed across 33 art categories in the Olympic Games. While medals are no longer awarded, the legacy still lingers in Olympic posters, mascots, and graphic designs seen in the modern Games.

Though the story of art in the Olympics has faded from public memory, for those who know it, it remains a fascinating chapter in sports history – a time when artists and athletes shared the same podium, uniting physical strength and aesthetic beauty under the global spirit of competition.